This

article was first published in Ayrshire Notes 31 (2006),

4-9. |

James

McAdam of Waterhead (c.1716-1770), father of John Loudon McAdam,

built Lagwine (also 'Lagwyne') 'castle' at Carsphairn, resided

for a time in Ayr - reputedly at the time of John Loudon's birth - and died at Whitefoord

House. This much is generally accepted. Through a study of window

tax records [WTR], these movements have been traced and his periods

in residence at his various houses identified within the limits

of the six or twelve month taxation periods. |

|

The

ruins of Lagwine, March 2006. photo David Courtney McClure |

Window

tax was first levied in Scotland under an Act

of 1746 for taxation of 'Houses, Windows or Lights'. [1] The annual charge on a house with 10 to

14 windows was 6d for every window; with 15 to 10 windows it was

9d; and with more than 20 windows it was 1s. Thus for 14 windows

the tax due was 14 x 6d or 7s; for 15 windows it was

15 x 9d or 11s 3d. Where there were fewer than

10 windows a house tax of 2s was payable, but houses in Scotland were exempt.

In 1757 this exemption was restricted to houses with no more than

5 windows or lights, and house tax was reduced to 1s; houses with

6, 7, 8, or 9 windows were liable to house tax of 1s. [2] However in 1761 window tax was extended to houses

with 7, 8, or 9 windows: up to 5 windows no tax was payable. with

6 windows house tax of 1s was payable; and with 7 or more windows,

window tax. [3] An act of 1778 exempted houses worth less than

£5 a year, or £10 in the case of farmhouses. [4] The charging periods appear in some cases as

Whitsunday (15th May) to Martinmas (11th November) and Martinmas

to Whitsunday, in others as May to November and November to May.

At other times a period of a year is recorded, Whitsunday to Whitsunday

or May to May. [5]

The tax was payable by occupiers rather than

owners, and this is the particular advantage of the WTR. In May

to November 1753, the first period for which complete WTR have

survived, James McAdam occupied a house of 44 windows in the parish

of Ochiltree, described in the WTR as 'Lord Glencairn's house';

such identification of an owner is uncommon. Ochiltree House,

the mansion house of the estate, was by far the largest of the

four houses in the parish liable for tax (the number of windows

being taken as an index of size). It was jointly with Kirkmichael

House the 24th largest in Ayrshire at the time. McAdam's wife

Susannah, as granddaughter of Sir John Cochrane of Ochiltree,

had a strong family connection with the house. The first earl

of Dundonald had given the estate of Ochiltree, comprising about

three fifths of the parish, to his second son, also Sir John Cochrane.

However in 1737, Charles Cochrane sold it to James Macrae, a former

governor of Madras. Macrae, who had no family of his own, had become the benefactor

of the family of a cousin who had married Hugh McGuire, and he

settled the estate on their daughter Elizabeth on her marriage

in 1744 to William, thirteenth earl of Glencairn.

[6]

By 1797-1798 Ochiltree House (NS 510 212)

was apparently absent from the WTR, but the 14-windowed house

occupied by the Rev. Thomson was probably the habitable portion

of the larger edifice. He described it as 'an old mansion house,

situated at the east end of the village of Ochiltree, which is

the present residence of the minister, the manse being entirely

in ruins.' [7] By 1856 the house had been derelict for many

years: 'Ochiltree House, the property of the dowager Lady Boswell,

is a plain building, three storeys high, with crow-stepped gables

and a slate roof. It is in bad repair and becoming ruinous. Attached

to and occupying the E front of the mansion is a ruin, about 12ft

high, divided into apartments. Its walls are about 6ft thick and

part of an arched roof is still entire. It has the appearance

of having been a castle of some strength. It must have been unoccupied

for a long time as there are large trees growing within it.' [8] The house was brought back into habitation later.

There are records of additions to the building in 1891, possibly

for James Angus, coalmaster and elder brother of Robert Angus

of Ladykirk. [9] He was the occupier c.1900 and until his death

in 1902.

Alexander Murdoch in 1921 called it the 'Big

House', standing 'in a delightful situation at the junction of

the Lugar and the Burnoch'. He continued,

Though the building is tall and plain-looking,

with narrow windows and pointed gables, its architectural defects

are fully compensated for by the beauty of its situation at

the meeting of the waters.

The present structure is over two hundred

years old. It was erected on the site of a still more ancient

edifice, whose foundation walls can even yet be traced. Within

the recollection of some of the older people of the village,

a wing of the former castle protruded at right angles from the

south side of the present house, and with its massive, ivy-covered

walls and attenuated, broad-arrow windows formed a characteristic

relic of the troubled times when every house of any importance

had to be built after the fashion of a fortress. [10]

Ochiltree House was pulled down in 1952. [11] It was reported in 1981 that the site had been

completely cleared, and was occupied by a road and by a new 'Ochiltree

House'. [12]

In November 1753 to May 1754, and May 1754 to

May 1755 McAdam continued in Ochiltree parish. but in a house

with 18 windows. Glencairn's house was 'not inhabited', and thus

no tax was due on it. The last period for which McAdam is found

in the Ochiltree WTR is Whitsunday to Martinmas 1755, for which

his name appears as occupier against the house of 18 windows,

but it was 'not uninhabited'.

But what of Waterhead? McAdam's barony of Waterhead

was in the Kirkcudbrightshire parish of Carsphairn. There was

no entry for a house of that name in the WTR for Whitsunday to

Martinmas 1753, when three dwellings in the parish were taxed,

nor in any subsequent period. [13] This indicates a house of no more than 9 windows.

Waterhead was a mean dwelling compared to McAdam's Ochiltree homes.

It was also very remote, lying about 3½ miles north of Carsphairn

beside the Water of Deugh. McAdam's new house of Lagwine, just

over half a mile from Carsphairn church and on the rutted unmade

road from Dalmellington, appeared first in the WTR in Martinmas

1754 to Whitsunday 1755. It was recorded as having 13 windows

and being 'not finished'. In subsequent periods it was 'not inhabited'.

McAdam was not liable for tax there until Whitsunday to Martinmas

1757.

From May 1755, when he left Ochiltree, until

Whitsunday 1757, when he occupied Lagwine, McAdam could have been

residing at Waterhead, and not troubling the tax records. He

was, however, occupying a house of 17 windows in Ayr. [14] He was there first in May 1755 to May 1756 and

remained until May 1759 to Whitsunday 1760. John Loudon was born

on 23rd September 1756, during McAdam's time

in Ayr and when Lagwine was 'not inhabited'.

The house McAdam occupied in Ayr has been identified, possibly only by

tradition, as 'Lady Cathcart's house' in Sandgate, though there

is ambiguity over the identity of the lady in question. According

to the plaque on the building, the house was owned by Lord Elias

Cathcart, and it is named after his widow. [15] However, there was no 'Lord Elias Cathcart'.

Charles Schaw Cathcart (1721-1771) succeeded as ninth earl of

Cathcart in 1740, and was the sole Lord Cathcart at that time.

The earls of Cathcart were significant landowners in Ayrshire,

their estates including Sundrum and Auchencruive. With the disposal

of the latter to Richard Oswald in 1764, Schaw Park in Clackmannan became the family seat.

In May 1755 Charles Cathcart was the owner of an uninhabited 18-windowed

house in Ayr. Another 18-windowed house was occupied

by Baillie Cathcart: i.e. Elias Cathcart, a tobacco and wine merchant,

who was admitted a burgess and guild brother of the Royal Burgh

in 1733, and served as provost in 1757-1759. [16] James McAdam is listed separately as the occupier

of a house with 17 windows. Thus he lived neither in the house

then occupied by Elias Cathcart, nor in the uninhabited house

belonging to Lord Charles Cathcart, though since the owner of

the house he did occupy is not recorded, it could well have been

the property of either of them, or, indeed, it could have belonged

to someone else entirely.

As to 'Lady Cathcart', it may be noted that

the widows of untitled landowners were frequently termed 'Lady'.

Georgina Keith McAdam, daughter of John Loudon McAdam, later recorded

that 'Great Grandmama was a very stately lady and never gave up

her title of Lady Waterhead', a dignity rather than title arising

from the barony of Waterhead. [17] The 1755 WTR show that Ladies Brownhill, Trochrige,

Achenskeith, and Dunduff, none of them the widows of lords, baronets,

or knights, were also then occupants of houses in Ayr. Elias Cathcart acquired a small estate

in Alloway; this, and his important position in the burgh, appears

to justify his widow's courtesy title.

Lagwine proved to be a short-lived venture. [18] For the year Whitsunday 1757 until Whitsunday

1758 he was liable for tax on 13 windows. In the following period,

Whitsunday to Martinmas 1758, the record shows 8 windows and only

house tax was levied. A window could be discounted for tax only

if it were 'stopped up', which required it to be filled with stone

or brick, or plaster or lath, or with the same materials as on

the outside of the house. Just a year after entering his new

'castle' at Carsphairn, McAdam had taken steps to reduce its size

or to stop up 5 of its windows. Until Whitsunday 1760 he was

also paying tax on his house in Ayr. He continued paying house tax on Lagwine until Whitsunday 1763,

following which it disappeared from the records, having been destroyed

by fire in December 1762.

In September 1762, James Boswell visited Lagwine,

being a cousin of James McAdam's wife, and played with the children,

one of them the six-year-old John Loudon. Three months later

Boswell's tutor, William McQuhae, wrote to advise him that

the house at Lagwine, which afforded you a

hospitable retreat on your road to Galloway was burned to ashes about ten days ago. With great difficulty the

children's lives were preserved by their leaping naked out of

windows two storeys high. Not a single paper nor piece of furniture

could be saved from the flames. It is a prodigious loss to

the worthy gentleman, particularly as his bills and rights of

his estate are all destroyed. [19]

D.S. Ramsay, the nephew of General Sir John

Shaw Kennedy, himself a nephew of John Loudon McAdam, recorded

the fire in a memoir dated 1883, in which he makes John Loudon

rather younger than his six years. [20]

While still in the cradle, [John Loudon McAdam's]

father and mother, going on a visit to Edinburgh left him at their house of Lagwyne,

parish of Carsphairn, in charge of his elder sisters and a nurse.

During the parental absence the house took fire as evil chance

would have it, in the middle of a winter night, the flames gaining

so rapidly that the family had to seek refuge (some of them

in their night-dresses), on the bleak hill side covered with

snow. While from this unenviable position they stood helplessly

gazing at their house enveloped in smoke and flame, it was observed

with horror that the little one in the cradle had been forgotten.

The nurse crying out "Am I going to add murder to arson"

(it seemed her carelessness had been the cause of the fire),

rushed back and at considerable risk to herself, saved her charge

from the flames. To reach the nearest place of shelter, the

party now homeless wanderers, carrying Loudon in their arms,

had to make their way as best they could on foot, over half

a mile of dreary upland rendered still more desolate by snow

and darkness. After a weary tramp and much suffering they reached

at last the manse of Carsphairn, where they were hospitably

received by the good minister.

McAdam did not rebuild Lagwine, and his whereabouts

for over a year until Whitsunday 1764 are not recorded. It is

then that the WTR first show his occupation of the 35-windowed

house in Straiton parish belonging to Sir John Whitefoord of Whitefoord.

The house was named 'Blaehane' in the WTR for 1756, but was later

given the name of Whitefoord, under which the estate is depicted

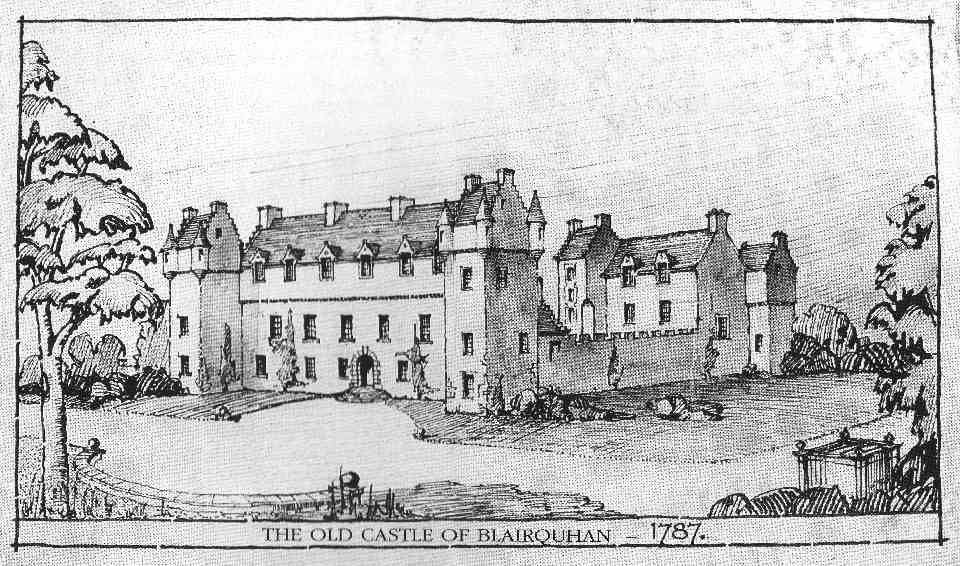

on the Armstrongs' 1775 Map of Ayrshire. [21] There is an engraving belonging to the estate

entitled 'The Old Castle of Blairquhan - 1787; given that the

date is 12 years before the sale, it is surprising that it is

named 'Blairquhan' rather than 'Whitefoord'. According to Davis, the castle 'formed a complex of considerable

size and magnificence'; it was much grander than McAdam's circumstances

warranted. [22] Sir John sold the estate in 1798 to Sir David

Hunter Blair, under whom it reverted to a form of its earlier

name, Blairquhan. He had a new mansion erected in 1820-1824,

in which only a few details of the former building have been retained. [23]

James McAdam remained at Whitefoord until his

death on 20th August 1770. [24] A. Cochrane, the niece of his widow Susannah,

wrote of the circumstances of his passing to her brother in December:

I was also at my Uncle McAdam's sometime,

who then resided at Whitefoord & [He] was very ill of the Gout,

which ended in a Dropsy and at last cut him off about three

months ago. He was generally thought an Extravagant Man, and

from that 'twas apprehended his circumstances might be embarrassed.

But it turned out otherwise at his death, for fortunately for

my Aunt & 5 [sic] daughters he has left unmarried

he died worth about 6 or £7000 & to each of the girls he

left £500 the rest to his only Son Loudon a promising boy yet

at school. [25]

|

|

Whitefoord Castle (The Old Castle of Blairquhan, 1787)

reproduced from the Blairquhan guidebook by permission

of Patrick Hunter Blair. |

It might have been speculated that the elimination

of windows at Lagwine, thus reducing the tax liability, was

an economy measure. His reputation however, and the grand

houses he occupied in Ochiltree and Straiton, suggest that

there may have been another cause.

During his decline McAdam sold his Waterhead

estate to the earl of Stair. [26] John McAdam of Craigengillan, a distant relation

but a close associate, acted for him in the business. Craigengillan's

intentions may not have been honourable: a few years later

he purchased the estate from the earl, a matter which gave

rise to considerable resentment on the part of the Waterhead

McAdams, who felt that they had been cheated out of their

inheritance.

David McClure

Postscript concerning Ochiltree House

I had the following notes on file but did not remember them

until after publication:

1) NLS Catalogue of Scottish Postcards: Pc.8/A101, 'Ochiltree

House, where John Knox was married.'

2) Shaw (1953), 55: 'is in the course of being demolished.'

[1] 20 Geo. II c.3, 1746, National debt.

[2] 31 Geo. II c.22, 1757, Pension duties.

[3] 2 Geo. III c.8, 1761, Window duties.

[4] 18 Geo. III c.26, 1778, House duty.

[5] National Archives of Scotland [NAS], Window Tax records for Ayrshire:

E326/1/11, May 1753-May 1759

E326/1/12, May 1759-May 1764 (May-November 1763 wanting)

E326/1/13, May 1764-April 1773

E326/1/14, April 1773-April 1782

E326/1/15, April 1782-April 1789

E326/1/16, April 1789-April 1798 (April 1795-April 1797 wanting).

[6] The Scots Peerage, vol. IV (Edinburgh, 1907), 250-252; Alexander Murdoch,

Ochiltree: Its History and Reminiscences (Paisley, 1921), 74-79.

[7] Old Statistical Account (1791-1799), vol. V,

Rev. William Thomson, Ochiltree, 448.

[8] Ordnance Survey Name Book, 1856.

[9] Information from Rob Close: Building Industries, Vol 1,

no 12, March 1891, and Vol 2, no.1, April 1891, also Ayr

Advertiser 19 February 1891; also the notes on James Angus.

[10] Murdoch, Ochiltree, 47-48.

[11] Information from Rob Close.

[12] Information from RCAHMS database.

[13] NAS, Window Tax records for Kirkcudbrightshire, E326/1/59-60.

[14] NAS, Window Tax records for Ayr: E326/1/134, March 1748-September

1748, May 1760-April 1798 (May 1753-May 1760 see vols. 11

and 12; April 1784-April 1785 see vol. 217; April 1795-April

1797 wanting).

[15] The full text of the plaque is: 'Lady Cathcart's House. One of

the oldest secular buildings in the medieval Royal Burgh and

now among the rarest in Scotland, it was remodelled in the

18th century, when it is said to have been owned by Lord Elias

Cathcart after whose wife it is named. John Loudon Macadam

[sic], the famous road engineer, was born here in 1756.

For a few years in the 1850s it was the Ayr branch of the City of Glasgow Bank which failed in 1878. The building

was purchased by the Bank of Scotland in the 1980s. In 1988,

Kyle and Carrick Civic Society campaigned to save the building

from demolition. The Bank of Scotland then generously donated

Lady Cathcart's house to the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust

and extensive repairs, principally funded by Historic Scotland,

Enterprise Ayrshire, South Ayrshire Council and the Civic

Society were completed in 1996.'

[16] Alistair Lindsay and Jean Kennedy, eds., The Burgesses and Guild

Brethren of Ayr 1647-1846 (Ayrshire Federation of Historical

Societies, 2002), 126; John Strawhorn, The History of Ayr:

Royal Burgh and County Town (Edinburgh, 1989), 115, 284.

[17] Georgina Keith McAdam, 'The History of the

Waterhead McAdams and the McAdams of Craigengillan'. (unpublished

manuscript, 1854).

[18] An investigation and partial excavation of the ruins is reported

by Alastair M.T. Maxwell-Irving, 'Lagwyne Castle (NX 558 939)', in Transactions

of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian

Society, Third Series Vol. LXXI (Dumfries, 1996), 163-165.

[19] This letter dated 27th December 1762 is cited in Frederick A. Pottle, ed., Boswell's London

Journal, 1762-1763 (Yale, 1950), editor's note to entry for 14-15th

September 1762.

[20] Mgr D.S. Ramsay, 'Biographical Sketches of some Ayrshire people

of the last and present centuries', 1883, 59-60; unpublished

manuscript in Carnegie Library, Ayr (South Ayrshire Libraries).

[21] Captain Armstrong and Son, A New Map of Ayrshire, comprehending

Kyle, Cunningham, & Carrick (1775).

[22] Michael C. Davis, The Castles and Mansions of Ayrshire (Ardrishaig,

1991), 181.

[23] Rob Close, Ayrshire & Arran: An Illustrated Architectural

Guide (RIAS 1992), 188-189.

[24] Scots Magazine, XXXII (1770), 458.

[25] 'A. Cochrane', Castle Canon, to her brother [name unknown], 1st

December 1770, Shaw Kennedy MSS., cited by Spiro, 'John Loudon McAdam'. McAdam

actually had 7 unmarried sisters at the time.

[26] An account of this will be given in a subsequent article.

|

|