|

|

|

|

Articles |

|

Copyright notice: Links to this site are welcomed. However none of the material on the site may be duplicated in any form. The copyright of the articles is the property of the authors. Copyright of the web pages is the property of David McClure. |

Ayrshire Stallion Leaders

by Jim Mair

When farming in

After the war, when the tractor and lorry replaced the heavy horse, many thousand draught horses were slaughtered and left the scene as if overnight. In 1947, one hundred thousand were put down and a similar number the following year. [i] The figure eventually ran in to millions as the transfer to motor transport increased. The Clydesdale had been a daily presence on the roads and a wonder to every watchful child. They had graced the landscape for generations. Farmers, farm workers, delivery men and roundsmen had sustained with them an affair of mutual devotion throughout their working lives.

I had interviewed a number of surviving grooms in Ayrshire in the 1980s. Three of them - Ben Boyce, Bob McClymont and John Fleming, all then living in retirement - were happy to draw upon memories of lives of achievement and much pleasure.

Ben Boyce was employed by J & R Smith, of Nether Newton, Newmilns, as a stallion leader from 1936 until 1946. He travelled two seasons in County Durham, to Chester-le-Street and Seaham Harbour, and 'liked it fine.' In 1944 he remembered 1,780 horses going through Lanark market in four days. The grooms attending took their refreshments in 'The Silver Bell', where stories and experiences were shared. In the train to the great Scotstoun Show, Ben Boyce recalled a minister coming into the compartment and saying, 'I suppose you gentlemen are in the horse business; you'll not be able always to tell the truth.' One of them called Davie Riddell replied, 'It widnae be sae bad if lees could dae it.' The care of stallions and their presentation to the mares was a highly skilled job, not always apparent to ministers and other laymen.

Service charges varied between breeders. When Ben travelled to Mull in 1940 he journeyed light with a coat and oilskins, and a notebook. Food and laundry would normally be supplied at the farms. Fees were between £2 and £3, with better horses perhaps up to £5. When asked about grooms with a horse companion, he recalled only one, an old fellow in County Durham with his own old stallion called Jolly Boy. He travelled with a pony and Ben Boyce found it strange watching them approach, the groom on his pony with the stallion alongside. He put it down to him being too old to walk the great distances.

Bob McClymont was a stallion leader with the breeder George Alston of Loudounhill, from 1936 until his last walking season in the Crieff district in 1949. A groom's fee was 2s 6d (12½p), rising to 5s (25p) after the Second World War. Sometimes an unofficial fee could be earned on the quiet. An old groom told him when he started, 'Ye're nae dampt use if ye cannae get a new suit o claes and a pair o buits oot o it.' Mr McClymont believed his job was like a disease: you became attached to the horses and foals and knew them all their lives. Grooms had a pride in their work; when you first came out leading a stallion 'ye stuck your kist oot. Ye were a man.'

Dressing and grooming was part of the stallion leader's

duties. Raffia plaits were attached to the horse's mane until after

the shows and inspection by the farmers. Purely decorative, they

might help to give the right signals to a group who could be a delegation

from an agricultural association, looking for a horse for the travelling

season. Bob McClymont enjoyed the life,

and in the walking season he was always welcome in the Ayrshire dairy

farms. The folk were interested in horses and farm workers are in

the kitchen with the family. In the north-east of

The scale of the work can be judged when between Turnberry and Girvan a stallion would serve 85 mares. This was only one estimate given by the breeder George Alston of Loudounhill. Other stallions might be working in the same area. With the horses you had to be in control, but without being cruel. One groom, for example, spoiled a very good horse named Cornfallow by overworking it. Bob McClymont got it back after a season and had no end of bother with it, as it had established dominion over the groom. Horses sense your feelings if you are scared or tentative, he said. An unlikely candidate for stallion leader was a wee fellow called 'The Gas', a terrible blether, who came through from West Lothian to lead a stallion there. On seeing the diminutive figure with the huge stallion disappearing up the road to Darvel station, George Alston turned to Bob, and said, 'What dae ye think will happen?' The Gas was full of confidence, but never came back for a repeat season. The grooms also had their sad times. One leader went off to Galloway and his stallion died. Another was sent, and it died too. Still another was dispatched, but the groom came home with a halter. There was grass sickness in Galloway at that time.

The third informant of the great days of the Clydesdales was John Fleming, head groom at the renowned stud of James Kilpatrick of Craigie Mains. Kilpatrick had won the premier stallion prize, the Cawdor Cup, three times at the annual show at Scotstoun. The big event of the year was the stallion contest on the first Wednesday and Thursday in March. The trains went right into the showground. The grooms left Craigie on Tuesday to walk to Kilmarnock station with the horses. At Craigie Mains there were thirty to forty stallions with four or five mares for breeding and about three work-horses.

Fleming's own concern over the work was apparent. The stallions in earlier days were docked. It made them tidier and allowed better action; but the docking was very cruel and he said he never liked it. A big knife was used and the rump cauterised with a hot iron to stop the bleeding. Later, a vet's certificate was obligatory until it was finally legally condemned. Afterwards only the hair was cut.

Craigie Mains had horses travelling all over

The stallions had a working life of up to twenty years. The grooms travelled light with a razor in their pockets, and few other personal items. The stallion had a belt and the groom strapped his coat on top for bad weather, and possibly his leggings also. On each side would hang the horses' boots. These boots, made of leather, were in the shape of a foot, and with a buckle and strap. The boots were worn when the stallions were with the mares to avoid injuries. Horses travelled out from farm to farm in different areas. Those for Ayrshire, three in all, left Craigie Mains on Monday morning. One was the Kilmarnock horse; it would reach Barassie on Monday night, Springside on Tuesday night, Moscow on Wednesday, Carnell on Thursday and outside Ayr on Friday. It came home on Saturday or Sunday.

John Fleming's favourite stallion was Craigie Commodore. He served twelve mares one Monday and when John returned for foal money he had to collect for fourteen foals. He judged that a good stallion should have a bright eye, nice head, long neck, short back, big broad quarters, hough well up in the leg, short above, a deep belly and heart, and long silky hair. The fore legs should be well in below with big solid feet to carry them. Stallions were well-couthered during the season. They might get a bottle of stout with two eggs mixed in it at night, over and above their usual meals: quite often eggs would go a-missing on the farms.

It was a good life, better paid than other farm workmen, but the pitfall for the grooms on the road was their fondness of drink. They pulled up at pubs, and they drank at the shows. This brought about rivalry among them, and arguments began over stallions. One old Aberdonian that John Fleming knew who travelled in South Ayrshire used to get fu' every Saturday on his way back. He would be found lying at the side of the road with his horse grazing nearby. His boss put him in the car, but John had to bring the horse home. The old fellow, refuting the myth about Aberdonians, always gave him a sixpence the next day.

John Fleming's father was head groom at Craigie before him. When John started at eighteen there were

five grooms. When the stud at Craigie Mains

closed in 1961 he was the only groom remaining. The dispersal sale

after the death of Mr Allan Kilpatrick was held at Ayr Auction Mart

in October. Six horses were sold. Craigie

Gallant Hero went for 2,600 guineas; another, Craigie

Merrymen, followed what was then the trend and was earmarked

for

The great days were long gone since James Kilpatrick of Craigie Mains and William Dunlop of Dunure Mains, world class breeders, had their celebrated litigation over the ownership of the stallion Baron of Buchlyvie. The case went to the Court of Session, and finally to the House of Lords, which found in favour of Kilpatrick. The horse was sold at Ayr Mart, in 1911, for £6,500, which is possibly half a million pounds in today's money.

When John Fleming left Craigie Mains he believed the day of the Clydesdale stud was over. He found employment as a grain-store foreman, with steady hours and he was at home every weekend. His wife was happier with the new regime, but he himself thought that it could not be compared with his work with the horses and he was to have no more pleasure, as he said, in the birth of the wee foals.

Jim Mair

[i] See the chapter, 'The massacre of 1947' in Keith Chivers, The Shire Horse, 1976.

|

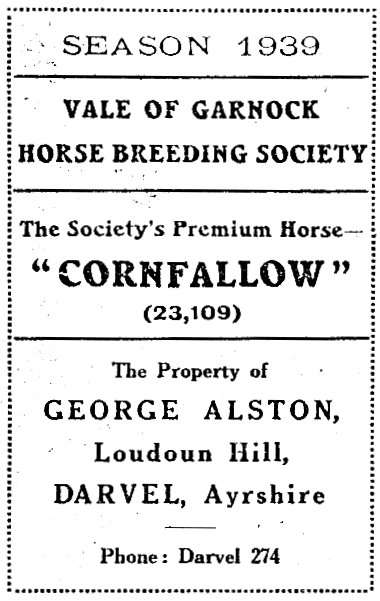

Walking Season, 1939. Cornfallow was offered to the Vale of Garnock Horse Breeding Society from George Alston's stud at Loudounhill. |

|

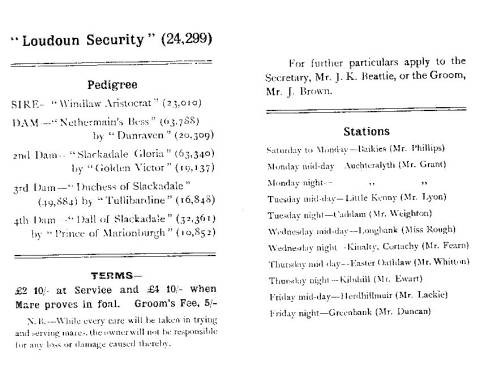

Season 1950, presenting Loudoun Security to the Kirriemuir District Agricultural Society showing its pedigree, terms and stations on the itinerary. Latterly stallions travelled by horse box to agreed collection points. |

|

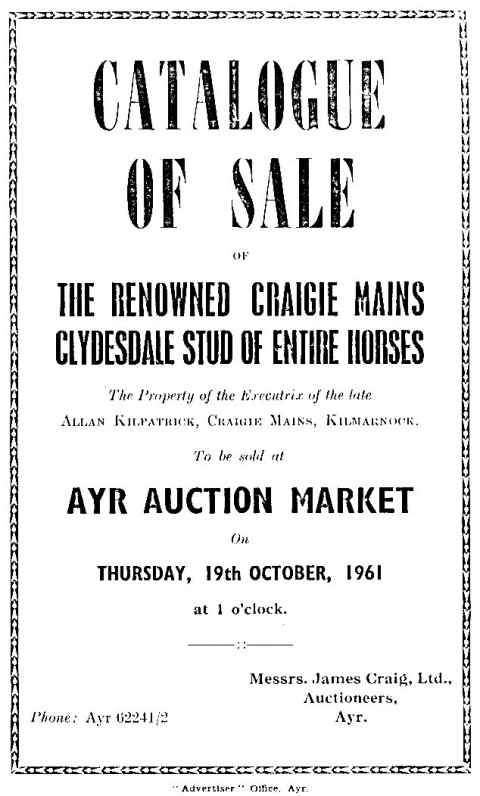

Catalogue

of the final sale of the Clydesdale stud of the Kilpatricks

of Craigie Mains. Craigie Merryman went to |

|

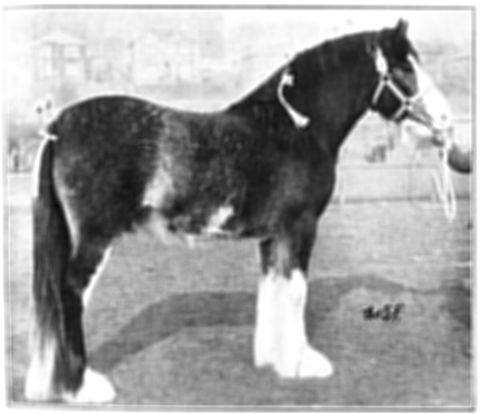

Craigie True Form owned by James Kilpatrick of Craigie Mains won the Cawdor Cup for the best male at the stallion show in 1948. |