|

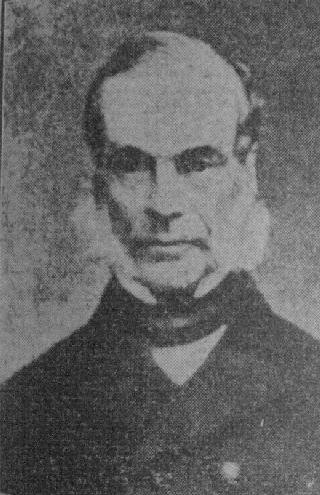

[above]

Thomas Macmillan Gemmell |

|

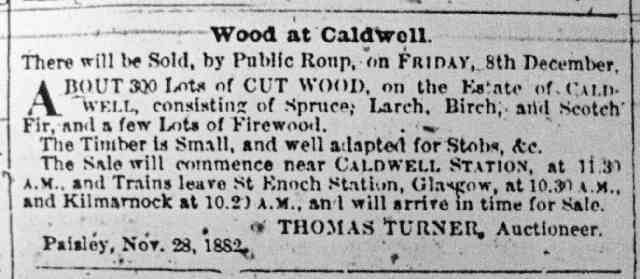

Advertisement

for sale of wood at Caldwell, Ayr Advertiser 7th

December 1882. |

|

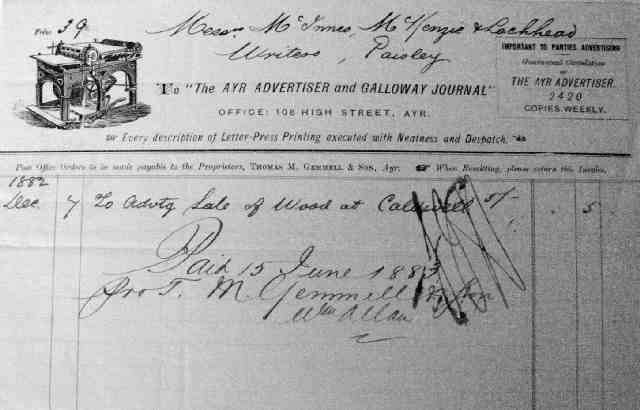

Invoice

for advertising sale of wood at Caldwell (private collection). |

|

It must be assumed that, having lost their case at law, McCormick

and Carnie bought Wilson’s share from his executors, for the

paper is continued thereafter under the imprint of McCormick

and Carnie. The paper appeared under this imprint for the

next 11 years or so, until July 1832, when William McCormick

died. His obituary says:

At Charlotte Street, Air, on the 29th ult, after a severe

and protracted illness, William McCormick, Esq., aged 41.

Since the year 1816, till within the last few months, Mr

McCormick conducted the ‘Air Advertiser’ and with what talent

and success ample proof is furnished by the popularity and

extensive circulation of that Journal. Prepossessing in

manners, calm in language, and vigorous in intellectual

faculties, he drew from the public a share of respect and

esteem which will long lead them fondly to cherish his memory.

His information, acquired by anxious and arduous study,

was extensive and well-digested; and he applied his knowledge

with such a singleness of heart, and discrimination of judgment,

as invariably enlisted the affections and admiration of

his numerous friends. But his soul proved too active for

its earthly frame – “Science self destroyed her favourite

son!” His body, exhausted by mental anxiety and exertion,

fell a prey to disease, so incident to the condition of

the studious; and he is thus, in the prime of life, removed

from this world, leaving behind a sorrowing widow and seven

helpless children to lament his early fate. The cause of

civil and religious freedom has, in him, lost an upright

and a powerful advocate. But, alas! To him “the uses of

the world are now ended.” “----- The dream is fled/ The

motley mask, and the great stir is o’er.”1

McCormick’s widow, Catherine Gemmell, inherited her husband’s

half share in the business, and the paper continued to appear

under the imprint of McCormick and Carnie for another 6 years,

until 1838. In October of that year, a notice appeared in

the Advertiser intimating that the partnership of McCormick

& Carnie had been dissolved, and that the business had

been sold to a new partnership, McCormick & Gemmell, of

which the partners were Catherine McCormick and her brother,

Thomas Macmillan Gemmell.2

Following his retirement from the Advertiser, Adam

Carnie pursued a new career as a ship-owner. He died, at his

house in Fort Street, Ayr, in October 1847.3

The purchaser of Carnie’s stake in the business, Thomas M.

Gemmell, had previously been an advocate in Edinburgh, but

had been the editor of the Advertiser since 1832,

having presumably come to the aid of his sister after William

McCormick’s death.4 A son

of Andrew Gemmell, an Ayr merchant, Thomas Macmillan Gemmell

was born in 1811. He married Anne Bell Telfer in June 18395,

and the couple had 3 sons and 4 daughters. With his introduction

to the firm, began the long association between the Ayr

Advertiser and the Gemmell and Dunlop families.6

Gemmell’s greater involvement in the management of the business

also sparked a number of changes in the working practices

of the newspaper.

Of these, the most obvious was the change of name. On Thursday

28th March 1839, the paper appeared under the title of the

Ayr Advertiser, or West Country Journal. Justification

for the change is given in an editorial (probably penned by

T. M. Gemmell):-

AIR or AYR. With mature deliberation, though not without

some regret, we have judged it proper to change our mode

of spelling the name of our good Town. Questions of Orthography

resolve themselves into two points – principle and practice;

and these, we are sorry to say, are often at variance with

each other. In the present instance, however, in adjusting

the claims of I and Y to the rights of burgearie [sic],

both claims will be found, so far as principle is concerned,

equally good, or rather equally bad – neither of them having

any etymological title to possession. In regard to practice,

the evidence in favour of the latter vowel is so overwhelming

that ‘The Air Advertiser’ was almost left alone in support

of the former … The 18th century brushed away the final

e from this [Aire], as well as many hundreds of words, and

in process of time, either modish affectation, or practical

utility, introduced the now almost universally received

distinction between the air we breathe and the Ayr we bathe

in – between the Royal Burgh of ‘Ayr’ and the ‘air’ of gentility

which sits with unaffected grace upon her ‘honest men and

bonnie lassies.’ Our Journal, in avoiding ‘to be the first

on which the new was tried’, has run some risk of ‘being

the last to lay the old aside.’7

The other important change was in the printing of the newspaper.

Late in 1838 the proprietors had announced that a new press,

a Carr & Smith’s Patent Double Acting Machine, would in

ready by the middle of January 1839.8

Previously printing had been done on a hand press [see Appendix

1, part 4], of which the capacity could not have been more

than 200 papers an hour.9

The machine introduced in 1839, and known as a ‘Belper’, was

still worked by hand, but was capable of printing nearly 1000

copies an hour; it remained in service until 1852.10

The paper continued to appear under the imprint of McCormick

and Gemmell until 1850. The final issue under this imprint

was that of 24th October 1850. The following week, it was

intimated in the paper that the partnership had been dissolved,

and the copyright of the paper and other assets had been sold

and transferred to Thomas M Gemmell alone.11

The impetus for this change was probably the decision of James

Fergusson McCormick, the son of William and Catherine, to

leave Scotland for Australia. He had been employed on the

paper as a sub-editor. The paper of 31st October 1850, which

contained this notice, was issued under the new imprint of

Thomas M Gemmell.12

Under Gemmell’s leadership, the Advertiser grew in maturity,

and assumed his personality and creeds. His, and its, political

creed became Liberalism of a moderate, progressive type, developing

from the Whig interests which the original paper had espoused.

The paper ‘has supported all measures of reform for which

it believed the country to be prepared’, but opposed, under

Gemmell and his successors, the demands of the Chartists in

the 1840s, and ‘certain Radical schemes in modern times which

it believed to be fraught with danger to the best interests

of the Empire.’13 Gemmell

himself had supported Whig, and then Liberal policies, and

was strongly in support of Parliamentary Reform. Once he became

proprietor and editor of the paper, ‘his opinions were confirmed

by contact with Richard Alexander Oswald of Auchincruive,

Thomas F. Kennedy of Dunure, James Campbell of Craigie, Hugh

Miller – for long Provost of the Burgh of Ayr – and other

leading men of enlightened and progressive ideas.’14

Under Gemmell’s ‘able and spirited management’15

the paper continued to thrive, with a great increase in circulation,

and became one of the leading newspapers in the south west

of Scotland.16 Gemmell

‘could wield a trenchant pen when he was provoked, or when

the discussion of any public matter called for it, but he

had formed a high idea of the functions and responsibilities

of journalism and studiously avoided rancorous personalities,

or anything that would inflict injury or pain on individuals

… [and] never ceased to impress on his assistants the duty

of exercising the utmost discretion in making statements and

comments.’17

Thomas Gemmell continued the pattern set by Hamilton Paul

of including literary and historical pieces, as well as straightforward

news. He, himself, contributed a number of these articles.

In the view of Hugh Allan, one of the best was his record

of ‘A Trip to London’, which appeared in a series of 14 articles

between 4th June and 3rd September 1846.18

The descriptions ‘were written in a graphic, racy style which

won for them great popularity.’19

Initially, Gemmell had acted as editor and reporter, but gradually

as the paper evolved into a business, and into something akin

to what we recognise today as a local newspaper, more and

more the paper relied on assistants, both in the print room

and the front office, and an unpaid battalion of local correspondents.

One early employee was John Moore, a native of Dundonald.

He had a pawky wit, not dissimilar to that of John Kelso Hunter,

and his lively and humorous pieces, ‘Matthew Moreland, the

Moleman’, were subsequently published in book form, and remained

in demand long after their initial appearance in the newspaper.20

Moore moved from the Advertiser in 1843 to found his own newspaper,

the Ayrshire Agriculturalist.21

By 1849 this had become the North British Agriculturalist,

and relocated to Edinburgh: Moore had however previously severed

his connection with it, and had emigrated to America, where

he achieved distinction as a journalist in Boston.

Other journalists from the 1840s whose names have come down

to us include John Willox, who was Chief Reporter around 1848-1849.

He, too, had a racy humour. He moved to a post in England

where one of his sons followed in his footsteps, with such

success that he was knighted and became an M.P. for Liverpool.22

The ‘racy humour’, noted in the works of Moore and Willox,

appears to have been too much for Robert Howie Smith, who

was taken on by the paper as an apprentice. ‘His connection

with the paper, however, was brought to a premature close

owing to his taking part in issuing a humorous poetical lampoon,

making fun of a number of well-known citizens, and he had

to finish his training elsewhere.’23

On the printing room floor itself we find James Johnstone,

foreman, and Alexander Guthrie, shopman, both of whom are

recorded in the 1845-46 Directory for Ayr.24

Following James McCormick’s departure for Australia in 1850,

the position of sub-editor was filled by William Howie Wylie

(born c.1833), who had been the Advertiser’s correspondent

in Kilmarnock. Wylie is best known for a series of sketches,

entitled ‘Ayrshire Streams’, which were subsequently published

in 1851 in book form. From Ayr, Wylie moved to journalistic

posts in Nottingham and Glasgow, before becoming a Baptist

Minister, and latterly founding and editing a weekly religious

paper, The Christian Leader. Wylie was succeeded

by William Smith, who came from Dundee but left after 18 months

or so to become proprietor and editor of the Whitehaven Herald.

Smith was succeeded by Hugh Logie Allan (1835-1908). After

schooling at the Newton Free Church School, Allan began work

in the offices of the Ayrshire Agriculturalist, but on 5th

March 1849 began work as a printer’s devil in the Advertiser

office.25 He worked up

to the reporters’ room, becoming an assistant reporter in

May 1853, and editor (under T.M. Gemmell’s watchful tutelage),

probably in 1858.26 Allan

was to remain as editor for almost exactly fifty years. The

beginning of this period of proprietorial and editorial stability

gives us an opportunity to look at changes away from the editor’s

chair.27

In August 1852, the size of the paper was increased from

four pages to eight. The newspaper had invested in a steam-driven

Double Acting Printing Machine, which meant that the paper

could now be printed more speedily, and could also be expanded,

both in the number of pages, and in the size of the page.28

The size would be ‘the size of the Times or, in other words,

to the largest size allowed by Act of Parliament.’ The proprietors

gave this explanation:-

In being the first of the Provincial Press of Scotland

to reach the maximum size - for, with the exception of the

Aberdeen papers, which can scarcely be called provincial,

no Scotch County paper has yet ventured on the largest sheet

– we have been prompted by the consideration that at certain

seasons, when advertisements are most plentiful, the space

left us for General and Local Intelligence, Agricultural

Information, Literature and Extracts from the Leading Journals,

&c., has been quite inadequate to the growing intelligence

of the Public, and to the vastly increasing importance of

the interests of Ayrshire: and we venture upon the risk

thus attending considerably increased annual outlay without

any advance on the price of the paper, in the confident

hope of a remunerative increase of Circulation. We have

indeed a guarantee for this, on which we reflect with some

little pride and satisfaction – that in the retrospect of

a nearly completed half-century, any efforts we have made

to ensure the Ayr Advertiser keeping pace with the spirit

of the age, have always been attended by encouraging public

support.29

Effective competition was one of the spurs: the number of

newspapers competing for trade in the south west of Scotland

continued to grow, while the growth of the railway network

was aiding the penetration of Glasgow and Edinburgh prints.

The proprietors of the Advertiser also admit that

the monthly and quarterly magazines, with their literary articles

and full reporting of political speeches, have stolen some

of their thunder. By introducing into the expanded Advertiser,

fuller political reporting and literature, coupled with local

news and advertisements, they clearly were hoping to prevent

a severe haemorrhage of readers.

This increased competition was due in part to the prosperity

of the 1850s, and changes in tax provisions. In 1853 Gladstone,

as Chancellor of the Exchequer, abolished advertisement duty,

and, subsequently, in 1855 he abolished stamp duty, thus demolishing

the two major restraints on newspaper growth. On the other

hand, technical developments such as the electric telegraph

enabled news to spread more quickly. The railways could bring

national newspapers, with up-to-date news, quickly to every

part of the country. To compete, and to compete with the growing

number of other local papers, a paper such as the Advertiser

had to find a new role, a new level to operate at. The result

of these changes was a noticeable growth in the amount of

local news, and a diminution of national news, especially

the almost verbatim reporting of both houses of parliament.

Hugh Allan began his association with the Advertiser

just before the advertisement tax was abolished. In his words,

he began when ‘the city papers did not invade much the province

of local journals. In about two months after I entered the

reporting room of the Advertiser in May 1853, the

advertisement duty was abolished, and within a year or two

afterwards the penny impressed stamp was done away with. This

opened the door to the new journalism.’ The local papers had

to adapt as best they could, ‘but the Advertiser held a position

of its own in having a large circle of readers who depended

on it for their weekly supply of general as well as local

news.’30

Top of page

Part 1

Part 3

Part 4

1 Air Advertiser,

Thursday 2nd August 1832, 4ef.

2 Air Advertiser,

Thursday 4th October 1838, 1e. The witnesses to the formal

document of dissolution were Hugh Henry, Robert Leyburn,

Joseph Erskine and James Robertson. Joseph Erskine (1795-1872)

was a writer (solicitor) in Ayr: ‘a most trusty advisor’

[Hugh L. Allan, ‘Ayr Fifty Years Ago And Since’, XI, in

Ayr Advertiser, Thursday 22nd May 1890, 5a.], while

Robertson cannot be conclusively identified. Henry and Leyburn

were employees of the paper: Henry (1815-1880) came from

Kilmarnock, where he had worked for James Paterson, before

joining the Air Advertiser as a ‘turn-over apprentice’

in 1833. ‘He was an excellent compositor’, and remained

with the Advertiser until 1843, when he took a

position as foreman with the Ayr Observer. Subsequently,

he established his own printing business, which survived

into the 1980s in Newmarket Street, Ayr. [Ayr Advertiser,

Thursday 16th December 1880, 5b] Leyburn switched careers

from compositor to clerk at the Fort Brewery, before drowning

in Ayr Harbour in 1845. [Kilmarnock Herald, Friday 15th

August 1845, 4d]

3 Ayr Advertiser,

Thursday 28th October 1847, 4g. The brief death notice gives

no further information on Carnie’s time at the paper, nor

does it suggest reasons for the change from newspaper editor

to ship owner.

4 Air Advertiser,

4th October 1838, 4b.

5 Ayr Advertiser,

Thursday 13th June 1839, 4f.

6 Thomson, ‘John Wilson’,

48.

7 Ayr Advertiser,

Thursday 28th March 1839, 4b.

8 Air Advertiser,

Thursday 27th December 1838, 4a.

9 When D. M. Lyon joined

the paper as an apprentice in the early 1830s, the wooden

press was still in use: ‘The paper was then printed on a

wooden hand press, and he used to tell of the hustle there

was on publication day to get the paper ready to send away

by the stage-coaches which were the only means of getting

them conveyed to different parts of the county.’ [Obituary

of Lyon in Ayr Advertiser, Thursday 5th February

1903, 5a.]

10 Allan, ‘Centenary’,

4f.

11 Ayr Advertiser,

Thursday 31st October 1850, 4e. The witnesses to Mrs McCormick’s

signature were James Fergusson McCormick, her son, and Anderson

Kirkwood. The witnesses to Gemmell’s signature were J F

Murdoch and Robert Ross. James F Murdoch was the procurator-fiscal

for the county, and a near neighbour of Gemmell’s in Racecourse

Road. Kirkwood and Ross cannot be satisfactorily identified.

12 Catherine McCormick

moved to Glasgow, latterly living at 2 Queens Terrace, Glasgow.

She died on the 5th February 1867 at Hastings, Sussex, where

she was presumably spending the winter months. Ayr Advertiser,

Thursday 7th February 1867, 5f.

13 Based on Allan,

‘Centenary’, 4f. The discussion of ‘certain Radical schemes

in modern times’ rushes us ahead of the narrative, but refers,

I believe, to the split in the Liberal party caused by Gladstone’s

support for Irish Home Rule. The Advertiser aligned

itself with those in the Liberal party, who became known

as Liberal Unionists, and who opposed Home Rule for Ireland.

This split led to a major realignment in national politics,

almost fatally weakened the Liberal Party, and allowed a

nascent Labour Party to emerge.

14 Ayr Advertiser,

Thursday 19th September 1889, 4c.

15 Allan, ‘Centenary’,

4f.

16 By the 1830s, other

newspapers were beginning to appear locally, and, more importantly,

to thrive. The most immediate rival was the Ayr Observer,

founded in 1832. [See Appendix 3]. By the end of the 1840s

there were also papers in Kilmarnock, Stranraer and in Kirkcudbrightshire,

all of which affected the circulation of the Advertiser.

17 Allan, ‘Centenary’,

4f.

18 ‘A Trip to London’

was published in book form in 1847. This trip was made at

a time when part of the journey still had to be made by

stage-coach and consequently the sketches ‘had a freshness

which similar things do not possess now-a-days.’ [Ayr

Advertiser, Thursday 19th September 1889, 4d.]

19 Allan, ‘Centenary’,

4f.

20 Moore’s pieces

were usually in the vernacular. William Donaldson, Popular

Literature in Victorian Scotland, Aberdeen, 1986, has

a long chapter, ‘The Scoatch Depairtment’, on ‘The Press

and the Vernacular.’

21 Correspondence

from Moore, from the years 1844-1845, seeking finance for

the establishment of the Ayrshire Agriculturalist exists

in the papers of Houstoun of Johnstone at the City of Glasgow

Archives, TD 263/293. This collection also includes an early

edition of the Ayrshire and Renfrewshire Agriculturalist,

no 17 of January 1845, which was printed for Moore by David

Guthrie, 1 High Street, Ayr. [TD 263/260].

22 Willox’s son was

Sir John Archibald Willox, 1842-1905, who was the M.P. for

the Everton Division of Liverpool from 1892 until his death.

Sir John began his career in journalism on the Liverpool

Courier. [Who Was Who, vol. 1 1897-1915, London,

5th ed., 1966, 769]

23 Allan, ‘Centenary’,

4f. R.H. Smith returned to Ayr in 1857 as the editor of

the Ayrshire Express; while there he also crossed

swords with William Buchanan of the Ayr Observer [see

Appendix 2 for Buchanan]. Smith also edited one of the earliest

of golf year books, The Golfer’s Year Book for 1866,

published by his company of Smith & Grant in 1866. In

1877 he acquired the Chelsea News. [Ardrossan

& Saltcoats Herald, Saturday 22nd December 1877,

5d]

24 [Ayr Observer

Office], Directory for Ayr, Newton, Wallacetown, St

Quivox, Prestwick and Monkton, 1845-46, Ayr, 1845.

25 Ayr Advertiser,

Thursday 26th March 1908, 5a.

26 Some sources suggest

that he became editor in late 1853. The date of 1858 is

based on the fact, quoted in Thomas Kay’s obituary, that

the combined length of Allan and Kay’s tenure of the editorship

was 79 years. Kay died, in post, in 1937.

27 These paragraphs

are based on Allan, ‘Centenary’, 4f.

28 There appears to

be no comprehensive history of the development of printing

presses in the United Kingdom. The first revolving type

presses, in which the type was placed on a cylinder which

rotated on a horizontal axis were developed in the United

States by Richard Marsh Hoe in the 1840s. A Swiss-American,

Ottmar Mergenthaler, developed linotype from the late 1870s,

but the development was resisted by compositors, and the

machinery only came into widespread use in the 1890s. Linotype

used a keyboard to create a unique type matter, which was

used once and then melted down for re-use, and so obviated

the need for the labour-intensive redistribution of the

type to the cases. It was reckoned that one linotyper could

do the work of five compositors. The only major development

for the first two-thirds of the 20th Century was the introduction

of electricity in place of steam power. The 1970s saw the

introduction of web-offset printing and photo-composition,

bringing many changes to the publishing world in their train.

This account is based on Peter Mercer, History of Printing,

in <http://ink.news.com.au/mercury>, a history of

the Hobart Mercury. [Seen 16th October 2003]

29 Ayr Advertiser,

Thursday 12th August 1852, 4d.

30 Ayr Advertiser,

Thursday 6th August 1953, 6e. The original source of this

quote from Allan has not been traced.

|